|

CRITICAL CONCEPTS

|

|||||||||||||||

|

FAIR TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT:

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS OF MAINSTREAMING? |

|||||||||||||||

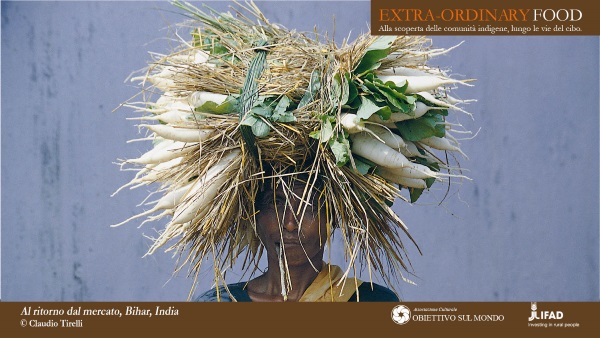

Ananya Mukherjee and Darryl Reed [*] One critical aspect of the current global crisis is the plight of small producers, particularly those operating in agrarian sectors. The extent of the problem is perhaps most dramatically illustrated by the recent waves of suicides among cotton farmers in India, in which thousands of farmers have taken their own lives[1]. One initiative that seeks to address the situation of small agricultural producers is the certified Fair Trade (FT) network. Initially purporting to offer an alternative form of trade relations, FT certification offered members of small producer organization higher prices for their produce than available at the world market, as well as providing several other benefits (e.g., advanced payments, a social premium for community development projects, technical assistance, long-term contracts, etc.). In recent years, however, the FT network has come under sharp criticism for allowing increasingly indiscriminate participation by corporate actors in FT. Critics argue that such moves have reduced the benefits that small producers receive and changed the very nature of FT. Advocates of such reforms, however, argue that they serve to grow the market and enable more small producers (and workers) in the South to participate in the benefits of FT. One surprising feature of the discussions surrounding the increasing role of corporations in FT is that for the most part they have not drawn upon development theory to frame the debates and analyse the consequences. In this article, we take a small step in this direction by analyzing different forms of FT values chains (distinguished in terms of levels of corporate participation) in terms of different development strategies. What is Fair Trade?

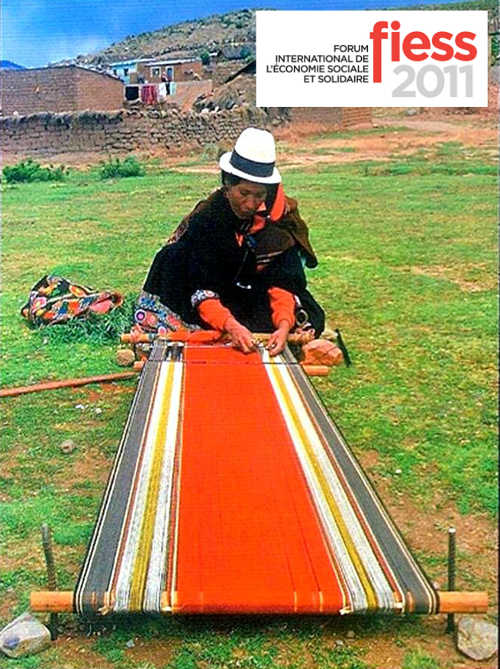

There are a variety of initiatives that are commonly associated with the genesis of certified FT. It has become common to distinguish between early "charity trade" (which involved ad hoc importing of handicrafts made by vulnerable groups, e.g., refugees, orphans, etc.), "alternative trade" (which was also based upon a critique of the dominant trade system and involved establishing alternative markets based upon solidarity which paid fairer prices) and "solidarity trade" (which had much in common with alternative trade but demonstrated a special concern with supporting governments and movements in the South that were promoting alternative forms of development, e.g., Tanzania, Nicaragua). One key feature that distinguishes certified FT from these earlier movements was its development of a label and standards which would guarantee Northern consumers that the certified FT products they were buying came from small producers and their purchases were supporting these producers in specific ways (Low and Davenport 2005; Hockerts 2005; Leclair 2002). The origins of certified FT can be directly traced back to a group Mexican coffee farmers. In 1983 members of 17 indigenous peasant communities in Oaxaca, Mexico came together to form the Uniµn de Comunidades IndÚgenas de la Regiµn del Istmo (UCIRI, Union of the Indigenous Communities of the Region of the Isthmus). While the development of this organization was a response to a variety of situations (including the role of local middlemen in the exporting of coffee), it is not co-incidental that the movement it set in motion developed during a time when a fall in coffee prices threatened to decimate small coffee producers. This drop in coffee prices, however, was not just a normal market fluctuation due to climatic conditions. Rather it was the result of the deregulation of the international coffee market, part of a larger trend of neo-liberal economic reforms around the globe which emphasized the need for "free trade" and the aligning of local prices to world prices. It was in this context of plunging coffee prices induced by neo-liberal reforms that UCIRI initiated a proposal to develop a certification process for fairly trade coffee. This resulted in the development of Max Havelaar Foundation in the Netherlands in 1998. Over the next decade a variety of other national certifying bodies would emerged in developed countries. In 1977, seventeen of these bodies joined together to from the Fair Labelling Organizations International (FLO) (VanderHoff Boersma 2009; Waridell 2002; Roozen and VanderHoff Boersma 2001). Fair Trade as an Alternative Market Before the development of a FT label, some small coffee producers were able to sell at least part of their coffee in alternative distribution outlets (worldshops, whole food stores, etc.) for higher than marker prices. The problem was that these distribution channels did not reach most consumers and so the amount of coffee sold was quite small. The producers of UCIRI realized that in order for them (and other small producer organizations) to sell more of their coffee at fair prices, they needed access to main stream distribution outlets, especially large grocery retailers. The development of a FT label was intended to help them get access to such a wider market (Hockerts 2005; Eshuis and Harmsen 2003). In their efforts to access this larger market, however, the small producers of Oaxaca were not merely trying to get higher prices for their coffee. As Francisco Vanderhoff Boeresma (2009), the Dutch priest who worked with the Oaxacan peasants to form UCIRI, explains, the main objective of the movement was to develop an alternative market, not just to attain access to the conventional market. And yet, in what seemed like an apparent contradiction, UCIRI was working with conventional firms. UCIRIs hope was that through the FT label they could work with conventional firms on UCIRIs terms. In effect, they were gambling that they could maintain the alternative trade relations they had with supportive alternative trade movements, while accessing conventional distribution outlets. Thus, from the start of certified FT there were inherent tensions between the compromises made to increase sales and the goal of developing an alternative market (Eshuis and Harmsen 2003). The alternative market that UCIRI and other producer organizations were advocating can be seen to consist of three principles - collective autonomy, justice and solidarity. The first of these principles, the collective autonomy of producers, is the fundamental governance principle of the alternative market. Such collective autonomy is institutionalized through alternative organizational forms such as producers associations and cooperatives (in which producers are democratically organized). This requirement of producer autonomy means that conventional business, which are governed by the principle of shareholder value maximization and hierarchical forms of control, cannot be central actors in the alternative market. The alternative market requires alternative social relations of production. The participation of corporations in the alternative market is best understood as a necessary concession to the reality of their dominance over consumer markets and a concession which should be limited to the retail sector (Vanderhoff Boeresma 2009). Second, in the alternative market social justice need to be reflected in a requirement that producers are compensated with a price that covers all of their costs, including - and especially - the social costs of production. One concern that arises in relation to this demand is that, insofar as the conventional market price does not reflect social costs, prices in the alternative market will inevitably be higher and alternative products may not be able to compete. If this is the case, as many critics claim, then participating in Fair Trade could actually have an adverse effect on small farmers. There are a couple of key points involved in addressing this question. On the one hand, it is important to note that it is not inevitably the case that a full-costing will result in higher prices than in the conventional market. While the full-cost price implies that farmers need to be paid more to cover all of their expenses, these increased expenses can still be offset by a combination of: a) a decrease in rents earned by middlemen and; b) the mark-ups included in conventional profit and revenue models (that are typically earned by large corporations). On the other hand, even if in practice full-cost pricing does lead to higher prices, this does not necessarily mean that fair trade products will not be able to compete. This will depend upon the willingness of consumers to pay a "premium" over the market price to cover the true costs of production. The practice of fair trade has shown that consumers are willing to do this, within certain bounds (Reed 2009; Raynolds 2000). This leads to the third feature of the alternative market, namely that it is built on relationships of solidarity between consumers and producers. More specifically, bonds of solidarity link consumers and producers by establishing an alternative set of social relations. These relations of solidarity need to be distinguished from models of support based upon charity. While charity and compassion may be commendable virtues, FT producers do not want relationships based on these motivations. As a movement that aspires to institutionalize shared principles of justice, producers believe that FT must be grounded in solidarity. This is not possible in the traditional market. Rather, it requires both producers and consumers to be organized through alternative institutions. As FT actors, producers and consumers need to be self-conscious participants in a global justice movement. The Mainstreaming of Fair Trade Relatively quickly after the introduction of the first FT label in the Netherlands in 1988, the aim of institutionalizing the principles of collective autonomy, justice and solidarity through an alternative market became marginalized within FT. This has happened as Fair Trade labelling bodies (often responding to pressure from Northern advocacy groups) have developed an over-riding interest in increasing the sale of fair trade products. This latter tendency has resulted in increased corporate involvement in FT, moving beyond the concession to include corporate retailers to extend to wholesaling, importing (licensing), processing and even production (through the use of estates instead of small producers). Not only has there been increased corporate participation, but what is particularly distasteful to many small producers has been the inclusion of corporations with especially bad reputations (such as Nestle, Wal-Mart, Dole, etc.). (Fridell 2007; Murray, Raynolds and Taylor 2006; Renard 2005). Elsewhere Reed (2009) has analysed the nature of corporate participation in FT. The key point that Reed makes is that as a result of increased participation by corporations, the practice of FT has become very diverse. This diversity can be analysed not only at the level of individual firms and organizations, but more significantly at the level of value chains. While Reed distinguishes four basic forms of FT value chains (see Figure 1), based upon a distinction between the dominant role of social economy and corporate actors, there are also other hybrid forms that can possibly be distinguished (e.g., forms involving only small businesses, forms with a variety of different types of actor in which none is dominant, etc.).

Figure 1: four variants of the Fair Trade Value Chain A basic concern which Reed expresses is distinguishing these different forms of FT value chains is that they are likely to operate in very different ways which lead to different development outcomes. One could well imagine, for example, that a wholly social economy value chain governed by relations of solidarity would engender a very different developmental trajectory than a wholly corporatized value chain. (It is important to note in this context that while there has been an increased diversity of practice within FT, all of these forms of production are stamped with the exact same label. This phenomenon often generates confusion among consumers, especially since the labelling bodies tend to associate FT with small producers and NGOs rather than large corporations). In the following section, we examine this question of how different variants of the FT value chain might map onto different development strategies. Fair Trade and Development

We noted above that between the social economy and corporate versions of the FT value chain, a range of other variants may exist. Now, which of these value chains are best for development? Obviously, development is a contested term and different notions of development view differently the roles of corporations and a whole range of other social actors, such as NGOs, foundations, social movements, national and local governments. We do not address the conceptual debate on development here. Rather, we contrast two development strategies which highlight different roles for corporations. The first is a corporate-led growth models which involves social regulation and the second is an approach that is sceptical of a significant role for corporations and instead focus on local resources and ownership. While we obviously endorse the connection between local resources and ownership, it does not fully exhaust the scope of development, when seen from a critical perspective. In our view, other dimensions such as democratic governance, participation, gender justice must remain equally important in a conceptualization of development (Mukherjee Reed 2008). Fair Trade as Endogenous Development As a model of local development, endogenous development (ED) advocates that local actors be viewed as the primary protagonists in the development enterprise. ED is based upon the experience that in our rapidly globalizing economy, specific regions ("territories") can draw upon local physical and human resources to develop innovative production strategies ("repertoires") that are grounded in SE relations and that enable local communities to react to external challenges in the global economy. A key factor is the establishment of local-global links which reflect shared values and allow for alternative commodity chains. Another important factor is the ability of local actors to organize to influence local public policy to make it more supportive of a SE model of production. These factors combine in a virtuous circle which enables territories to become competitive not only in a single sector or in a single market, but to build upon initial success and diversify the local economy and exploit new national and international markets (Garofoli 2002; Ray 1999). FT provides an important vehicle for pursuing a strategy of ED in several ways. First, FT requirements provide several key perquisites for ED, including a SE economic base and local-global links. Second, the actual practice of FT helps to generate other conditions necessary for an ED strategy: by increasing capacities of local organizations; reinforcing bonds of social solidarity; increasing civil and political participation among small producers and; educating northern consumers about the functioning of international commodity markets. Third, FT certification represents a form of innovation which creates new markets for local producers, markets based not merely on product quality and price, but on ethical considerations. The support provided to small producer organizations and the capacities that they develop through FT allows them in turn to extend their production and markets in new directions. This includes efforts by southern producers to introduce FT products to their own national markets (e.g., Mexico) and even to promote South-South FT. In addition, participation in FT provides a strong basis for diversification into other products. This can include new agricultural commodities, moving up the value chain through processing or branching off into not agricultural sectors such as manufacturing. FT can also promote other necessary capacities essential for ED, most notably perhaps increased engagement in the civic and political realms (Utting 2009; Jaffee 2007; Bacon 2005 Roozen and Vanderhoff Boersma 2001). Fair Trade as Socially-regulated, Corporate-led Growth As noted above, the widespread presence of corporate licensees and the introduction of estate production allows for an entirely corporate FT value chain which stands in stark contrast to the social economy variant. With the development of corporate chains, there is a move away from a model of local development to a model of corporate led growth in which the primary decisions affecting the development prospects of local people are made by large corporations. Such a model does not mean that workers are not better off under FT than they were previously. There are obvious material gains, in the form of the social premium and wages, as well as better working conditions (which FT certification requires). It is less clear, however, to what extent the stated FT goals of social and economic empowerment are likely to be achieved. Certainly, in relationship to social economy forms of FT production, workers have much less control and their channels for exercising control are limited to industrial relations mechanisms. Empowerment here means increasing the ability of workers to use the industrial relations process to negotiate a better contract (as well as initiating social development projects through control over the social premium). It does not, however, extend to larger decision-making questions regarding production, investment and marketing strategies (which are the realms in which the actual decisions as to whether to participate in FT are made). Nor does empowerment under this model seem to extend to developing the local economy in ways that the social economy form of FT production might (Renard and PÕrez-Grovas 2007; Fridell 2007; Shreck 2005). The follow-on effects from these consequences are that this model of FT production - insofar as it less effectively promotes empowerment and generates fewer resources for marginalized groups - will be less effective in stemming other problems in rural regions (e.g., outward migration) and promoting other key development goals beyond economic development (e.g., preservation of language, culture and traditional lifestyles). Conclusion

Underlying the complexity of FT practices are two stark realities. On the one hand, there are clear differences among the actors involved in FT as to what constitutes development. On the other hand, the power dynamics involved in the global political economy inexorably entail trade-offs and risks for those seeking to purse alternative forms of development. These two realities ensure that there will inevitably be differences of opinion and no easy answers. The irony, small producer organizations point out, is that in a network which they initiated and which purports to be concerned about their empowerment, they have not been full participants in the discussions. Rather, it has been Northern labelling bodies, which are not directly accountable to anyone but their own boards, which have determined the basic policy questions involving the role of corporations in FT (and, thereby, the approaches to development that are likely to dominate within FT) (Vanderhoff Boeresma 2009; Raynolds and Murray 2007). While producer organizations have made some advances in gaining access to representation on FLO in recent years, many producers are concerned that the key debates about the direction of the certified FT have already been decided in ways that may make them increasingly marginalized in a structure that was supposed to overcome their marginalization. References

Bacon, C. (2005) 'Confronting the Coffee Crisis: Cand Fair Trade, Organic and Specialty Coffees Reduce Small-Scale Farmer Vulnerability in Norther Nicaragua?', World Development 33 (3) Eshuis F., J. Harmsen (2003) Making Trade Work for the Producers: 15 years of Fairtrade Labelled Coffee in the Netherlands.The Netherlands: Max Havelaar Foundation. Available online at: http://www.fairtrade.org.uk/downloads/pdf/making_trade_work.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2007) Fridell G. (2007) Fair Trade: The Prospects and Pitfalls of Market-Driven Social Justice. Toronto: University of Toronto Press Garofoli G. (2002) 'Local Development Initiatives in Europe: Theoretical Models and International Comparisons', European Rural and Urban Studies 9 (3) Hockerts K. (2005) The Fair Trade Story. OIKOS Sustainability Case Collection, OIKOS Foundation for Economy and Ecology. Available online at: www.oikos-foundation.unisg.ch/homepage/case.htm (accessed on 18 April 2009) Murray D.L., L.T. Raynolds, P.L. Taylor (2006) 'The Future of Fair Trade Coffee: Dilemmas Facing Latin Americas Small Scale Producers', Development in Practice 16 (2) Ray C. (1999) 'Towards a Meta-framework of Endogenous Development', Sociologia Ruralis 39 (4) Raynolds L.T., D.L. Murray (2007) 'Fair Trade: Contemporary Challenges and Future Prospect', in L.T. Raynolds, D. Murray, J. Wilkinson (eds.), Fair Trade: The Challenges of Transforming Globalization. London and New York: Routledge Raynolds L.T. (2000) 'Re-Embedding Global Agriculture: The International Organic and Fair Trade Movements', Agriculture and Human Values 17, pp. 297-309 Renard M.-C. (2005), 'Quality Certification, Regulation and Power in Fair Trade', Journal of Rural Studies 21, pp. 419-431 Renard M.-C., V. PÕrez-Grovas (2007), 'Fair Trade Coffee in Mexico: At the Center of the Debates', in L.T. Raynolds, D. Murray, J. Wilkinson (eds.), op. cit. London and New York: Routledge Roozen N., F. VanderHoff Boersma (2001) Laventure du Commerce èquitable: Une Alternative Á la Mondialization par les Fondateurs de Max Havelaar. Paris: Jean-claude LattÕs Sainat P. (2008) Over 16,600 Farmer Suicides in 2007, India Together, December 21 Shreck A. (2005) 'Resistance, Redistribution and Power in the Fair Trade Banana Initiative', Agriculture and Human Values 22, pp. 17-29 Utting K. (2009), 'Assessing the Impact of Fair Trade Coffee: Towards an Integrative Framework', Journal of Business Ethics 86 (Supplement 1) Vanderhoff Boersma F. (2009) 'The Urgency and Necessity of a Different Type of Market: The Perspective of Producers Organized within the Fair Trade Market', Journal of Business Ethics 86 (Supplement 1) Waridel L. (2002), Coffee with Pleasure: Just Java and World Trade. MontrÕal: Black Rose |

|||||||||||||||

* Ananya Mukherjee and Darryl Reed are professors at York University in Toronto, Canada. They are currently spending their sabbatical in Bangalore, India. 1. In the past nine years some 182,936 farmers have committed suicide due to a combination of indebtedness, crop failure and the drastic fall in agrarian incomes (Sainath 2008). |

|||||||||||||||

Universitas Forum, Vol. 1, No. 2, May 2009

|

Universitas Forum is produced by the Universitas Programme of the KIP International School (Knowledge, Innovations, Policies and Territorial Practices for the UN Millennium Platform).

Site Manager: Archimede Informatica - Societû Cooperativa

ô