|

CRITICAL CONCEPTS

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

GLOBALIZATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

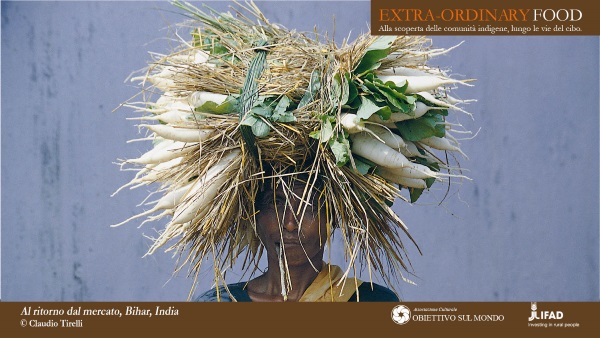

Sergio Boisier[*] and Giancarlo Canzanelli[°] Introduction: globalization and local development From the metaphorical standpoint, García Canclini (1999) has brilliantly described globalization as an “unidentified cultural object”; Baumann (1998) has referred to it as “a fetish, a magic spell, a key designed to open all the doors to all mysteries, present and past”; Boisier, recalling film-maker Luis Buñuel, has called it “an obscure object of desire” and “the discreet charm of the bourgeoisie”, and once again, García Canclini has said with incisive humour that “everything that is not the fault of the Corriente del Niño is the fault of globalization”. The “Globalist” and the “Territorialist” face each other in defending their arguments[1]. One side of the argument is that a global economy dominated by the big transnational corporations has arisen. The decisions of these corporations on the location of production or research and development (R&D) activities determine to a large extent what type of economic activity will be developed and where. Thus, the local territorial level becomes a kind of “dependent variable” in the innovative growth function. The other side of the argument[2], however, is that the local level is becoming more and not less important in terms of its contribution to innovation and high technology. The “globalizers” base their argument on the obvious fact that an important proportion of capital is becoming concentrated and centralized at the level of the international economy, as is confirmed by abundant data. It follows from this line of argument that local areas, regions and even whole countries are being redesigned in line with the global economy and its main actors: the multinational corporations. The “territorialists”, by contrast, point to the supposed reaction of consumption to the homogenization of the goods and services traded and the fact that many enterprises have responded by “flexible specialization”: a strategy of permanent innovation that seeks to adapt to incessant change rather than trying to control it. Flexible specialization goes hand in hand with small scales of production and with the need for “collective learning”, which is greatly facilitated by geographical proximity. The fact is that there is truth in both arguments. Globalization affects the size (and inevitably the location) of production units in two opposing and simultaneous ways. Economies of scale favour large size and territorial concentration, while the economies of flexibility demonstrated by Storper (1997) and those of differentiation favour small size and dispersion: but as small production units working in isolation have a high probability of failure, those economies also favour the formation of what are called industrial districts or value chains. A small empirical survey would be sufficient to show that the vast majority of people live their lives in a geographical space with a radius of not more than 500 kilometres. Within that space they live, form a family, work, obtain education and health, pass their spare time, and generally end up being buried there. It is easy to infer that, for any given individual, his possibility of realizing his own life project depends to a crucial extent on what happens over time in his everyday environment. The importance of the local dimension has also been underlined from the point of view of culture and identity, albeit within a globalizing dialectic due to the confrontation between the tendencies towards technological and cultural homogenization and defense of the individual and the community. The happy mean is expressed rather by Robertson’s neologism “glocal”: thinking global and acting local (for the enterprise) and thinking local and acting global (for the local area) The effects of globalization The recent global financial crisis has emphasized the effect of the profound transformation that Pilhon identifies in the shift from Fordist capitalism to “share capitalism”. The latter has three main characteristics: it is globalized, finance-dominated and part of the new technology trend. Moreover, it questions two basic aspects of Fordist capitalism, namely the importance of public policies and the priority given to internal markets and the national dimension. Within this new context, holders of financial capital, particularly as a result of processes of privatization, have become dominant actors controlling global finance: the size of international capitals' movement grows wihout control - and without a direct link with the worldwide increase in the level of exchanges of goods and services – basically because they are speculative and short-term. In this way the State returns to its ancient role of “État gendarme” that guarantees exclusively the security of goods, people and contracts because these are the sole commodities profitable for the market and for which the payment of a certain amount of taxes would be justified. Such regression and delegitimation, as Laville (1999) denounces, is also justified thanks to the bureaucratic and centralizing logic of redistributive institutions, and their lack of incentives for innovation, generating inaction, patronage, increased tariffs, worsening of working conditions, environmental damage and social exclusion. We now have the paradox of the “West” that, while searching for happiness and wellbeing, finds only mounting poverty, marginalization, wars and various forms of social discontent. Dal Bosco (2004) presents a single, emblematic datum: the annual income of the 225 wealthiest persons in the world is higher than the total amount of the annual incomes of 47% (2 billion 500 million people) of the world’s population. According to Stiglitz (2003), the “Washington Consensus” is one of the main causes of the present situation. By unconditional support to the liberalization of capital markets, and without considering the increase in international instability that this would have provoked, these actors have focused more on US interests than on the consequences of this process for poor countries. The result, in his opinion, has been that poor countries have provided the financial support for the US deficit; the US, incapable of living according its own means and resources and preaching market (and brain, capital, commercial) liberalization all over the world, administers internal affairs in the exactly opposite way: protectionism, nationalization of insolvent companies, patent protection (as the pharmaceutical industry is doing), etc. We can conclude that the prevailing mode of development is characterized by a dynamic of social exclusion and violence linked to the competition for the benefit of some to the detriment of others. Luciano Carrino (2005) distinguishes between different qualities of development as the ability to choose between “good” and “bad” development. To this end, he links development to its capacity to meet human needs. It can be considered “bad” (such as the currently prevailing mode) when it is concerned about meeting the needs of only a part of the population, leaving others frustrated and insecure, or when the solutions it provides can damage health, sow hatred and violence, undermine social cohesion, or irreparably destroy natural resources. On the contrary we have “good” development (or rather we would have it, if human development prevailed), when it does not create marginalization or exclusion and it tries to respond adequately to everyone’s needs, encouraging psychophysical wellbeing of individuals and peaceful cooperation between social actors and governments: good development improves collective resources and the diversification of material and cultural answers to needs, and it opts for ways of action that enhance the environmental, cultural and historical heritage. The kind of development, based on the actions of individuals and groups that consider themselves an elite, is exactly the version that the UN Millennium Development Goals project aims at overcoming, because of its disruptive consequences on social life: poverty, violent conflict, environmental destruction, disease, ignorance and lack of respect for human rights. Local Development In the current stage of the globalization process, the issue of local development can be considered from two different perspectives. As far as the first perspective, it is not difficult to demonstrate that local development always begins in one place (or several, but never in all places at once), it is a path-dependent phenomenon that evolves over time and it is always an essentially endogenous process (although its material base may be quite exogenous), always decentralized, and it always has a capillary-type dynamic “from the bottom up and from the centre outwards”. It will eventually produce - as a function of the territorial dialectic and of modernity itself - a development map which is rarely uniform but is usually in the form of an archipelago or, taken to an extreme, reflects a centre/periphery dichotomy. Local resources are the principal sources of work and income. Local fruits, vegetables and fishes, living and growing in diversified and thus unique environments, provide the world’s population with different kinds of food, each with its own identity and therefore in competition with the others. Furthermore, these primary goods can be transformed into natural medicines, preserves, and so on, that create added economic value, lead to small local enterprises and employment possibilities. When there is an increase in the capacity of local actors to organize and collaborate in value chains to improve the quantity and quality of their products, to commercialize them (not as such, but because they come from a specific place that has made that specific product possible), there is also an increase in the possibilities of finding employment and generating income: in this way, resorting to direct foreign investments that have the sole aim of enriching those – usually uninterested in sustainable local development - who provide the investment, can be avoided. This process, organized in an archipelago of local dynamics, combines to bring about national development - when governments are capable of steering, harmonizing and supporting it – and human wellbeing - when it offers the possibility to choose high quality and diversified goods and services. As far as the second perspective, the current global crises - such as increasing poverty, environmental damage, decreasing traditional energy resources, decreasing and poor-quality food production at global level in conjunction with a price increase that endangers people’s survival – need new and more effective answers, that can, in fact, better be provided at local level contaminations, and to promote successful economic activities? Vandana Shiva reminds us that today, the majority of people cultivating their own food die of starvation, while in the past they have always been able to store food supplies for harsh times. Hunger has become a structural problem because big multinational companies are buying all the production and small-farmers are not able to buy back from them almost anything. Therefore Shiva argues that biodiversity is the most flexible answer to climatic emergencies because of the capacity to adapt to change (Corona 2008). There are millions of plants, the most adequate response to hunger provided that they are cultivated where they are born and according to the knowledge of local populations. So far, though, the pressure put on small-farmers for producing new improved varieties and for buying new breeds of cattle and livestock has caused many local and traditional varieties to be abandoned and face extinction, while the massive use of pesticides and other chemical products has provoked severe environmental damage that endangers public health. Animal fertilizer and other agricultural residues can be stored in airtight containers called “digesters”: they produce biogas that can be used for heating, cooking and for many other purposes while simultaneously resolving the problem of the pollution produced by the manure itself. At local level it is possible to grow plants that produce liquid fuel, the so-called bio fuel. Solar panels, small hydroelectric systems and wind turbines can directly transform sunlight, water and wind into electricity; and this can be done on a very small scale so that communities can be independent in managing energy for local use, without utilizing fuel or polluting the environment. In this way local development contributes to global human development issues, whereas global crisis can find better solutions at local level (see fig. 1).Vazquez Barquero et al. (2001) point out that local development under globalization is a direct result of the capacity of the local actors and society to organize themselves and mobilize their efforts on the basis of their potential and their cultural matrix, in order to define their aims and explore their priorities and endogenous characteristics to obtain greater competitiveness within a context of rapid and far-reaching change. Fig 1. Local development and global development

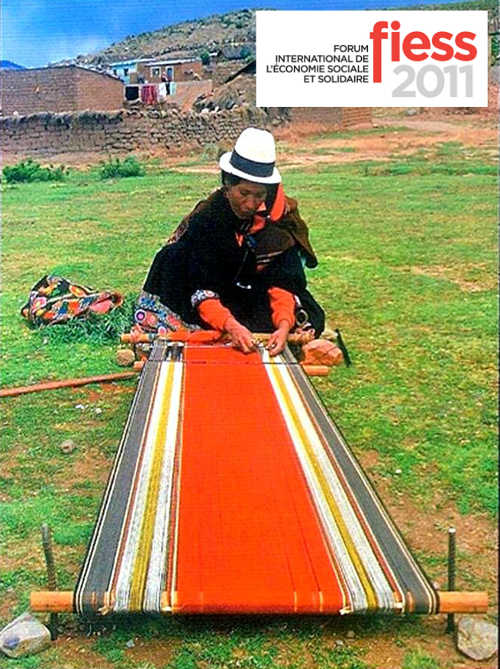

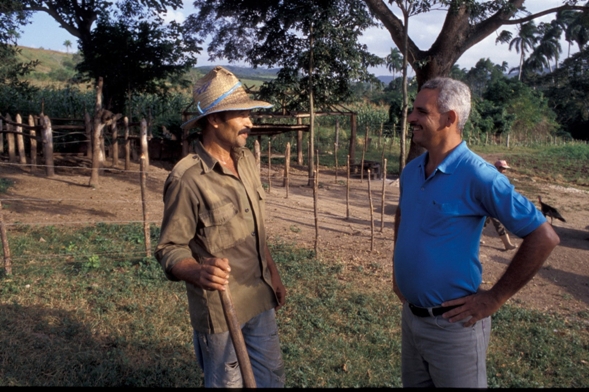

The endogenous nature of processes of territorial change should be understood as a phenomenon which operates on at least four levels that intersect and cross each other. Firstly, that endogeneity refers to or occurs at the political level, where it is identified as increasing local capacity to take important decisions on different development options, different styles of development, and the use of the corresponding instruments: that is to say, the capacity to design and execute development policies, and above all, the capacity to negotiate on the elements that define the setting of the local area. Behind this capacity, there must necessarily be a political arrangement that favours decentralization. Secondly, endogeneity also exists on the economic level, where it refers to the appropriation and local reinvestment of part of the surplus in order to diversify the local economy and at the same time give it a permanent base for long-term sustainability. On the economic level, endogenizing local growth means in practice seeking to reconcile the long-term strategic objectives of the local area with the long-term strategies of the non-local capital present in the area. Thirdly, endogeneity is also interpreted, at the scientific and technological level, as the internal capacity of a system —in this case, an organized territory— to generate its own technological drives for change, capable of bringing about qualitative changes in the system itself. Fourthly, endogeneity also exists at the cultural level, as a kind of matrix that generates a socio-territorial identity or adhesion, which is now considered to be of fundamental importance for development in the true sense. Local culture, whether recovered or newly built, requires an Aristotelian collective rhetoric: an ethos, a pathos and a logos. It may be stated that globalization, as a process which simultaneously seeks to form a single marketing space but multiple production locations, contains forces which promote the local dissemination of segments of various value chains, while also giving rise to forces that promote not only decentralization but also centralization and concentration. In view of this combination of effects, it may be said that globalization stimulates processes of local growth. Whether or not globalization stimulates highly endogenous processes of social change in some local areas will depend on the dialectics that come into play, and this will be linked with the devolution of capacities and areas of authority that the demands of competitiveness will tend to make the responsibility of the State. Clearly, in order to foster economic development processes aimed at the wellbeing of humanity, the local economic base and its endogenous potential constitute the necessary but not sufficient conditions, in particular when the variable to be taken into consideration relates to the sustainability of these processes. Sustainability necessarily includes: Sustainability over time Sustainability in terms of human development Amartya Sen (2000) places the concept of functioning as the base for wellbeing: “functionings” represent the physical and intellectual results obtained by an individual, such as health, nutrition, longevity, education, etc. and not those acquired through one’s income. Sen also proposes the notion of “capability”: while the former represents the actual attainments of an individual and are fundamental for wellbeing, capabilities represent potential attainments and are the basis for freedom - understood as the freedom to be and to do. Sen endorses the idea of freedom as the concrete ability to do something and to be someone, in opposition to a negative concept that sees freedom as the absence of formal obstacles. A disabled person who wants to reach a public building is certainly negatively free because no one can legally deny him the right to go there, but definitely is positively non-free (that is to say, practically not able) if the building is not handicap accessible. The same happens for a poor person looking for a job: no one denies him the chance to get a job, but the fact is that he is unable to find it. He is economically incapable! Without doubt both dimensions of sustainability concern development processes rather than the tangible results that stem from them (employment, poverty reduction, income, economic and social activities, and so on) and the capabilities to support, maintain, mix, innovate, link these processes on the outside with the aim of elaborating the most adequate answers to internal and external changes of context (crisis, disasters, alterations in needs, markets and technologies, evolution of the labour market, etc). Hence, a good policy for human development is to build or strengthen these capabilities through specific tools. Strategies and tools for sustainability: the experience of UN Human Development Programmes From the beginning of the 1990s, UN programmes of international cooperation for human development have first tested and then consolidated strategies and tools for territorial development[3] in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Balkans and Asia. Strategies for local economic development The strategies for sustainable territorial development, as addressed through these programmes, have always been based on the creation and strengthening of territorial relational capital through local partnerships that determine the strategies, priorities and objectives of socio-economic development. This relational capital developed from local working groups established in these cooperation programmes that take the decisions on planning activities and then continue working together, either within local development agencies or within territorial pacts or local committees for development. In order to pursue social, economic and environmental sustainability, human development programmes, through the ILSLEDA service network (International Liaison and Services for Local Economic Development Agencies), have developed the concept of sustainable competitiveness. This implies that in deciding on investment and economic development priorities local actors take into consideration three elements: competitiveness, territoriality and sustainability. Competitiveness is critical, because there is no development without a market for goods or services and the possibility of maintaining and increasing sales; territoriality is critical, because increasingly it is territories that are competing with each other, and less often individual enterprises thanks to the many factors that a territory can achieve through organization (scale production, innovation, transactions, tangible and non-tangible services, etc.); sustainability is critical because of the territorial capacity to maintain and improve the variables of its competitiveness and its competitive advantage. Strategies to develop the social economy or the “solidarity” economy, understood as economic forms that explicitly recognize the ethical and social dimension and that offer goods and services that are difficult to obtain through conventional markets, are inserted into this framework. The social economy groups together private companies that are democratically managed and operate for public benefit, both in terms of providing work (for disadvantaged people) and of supplying goods and services that respond to unsatisfied needs and that are unlikely to provide profits to the advantage of the owners. In the solidarity economy there is always a reconciliation between ends and means of production through businesses with ethical purposes that recompose various elements of a project for development, integrating them within alternative socio-economic models: from agriculture to food, to care for the environment, for urban and for public space, to the production of public goods and services, fair trade, systems and networks of local non-monetary exchange, to acknowledging cultural, productions and lifestyle differences, particular to every location (Magnaghi 2004). The experience of human development programmes has shown that a strategy of territorial development can be more successful if it is connected to national policies that are supportive of local development. These policies can be translated into mechanisms of coordination between different sectors to facilitate territorial development, in incentives for innovation, employment and small female entrepreneurship, into access to continuing education and in the promotion of national networks to exchange local experiences and tools. Moreover, the local-national network contributes to national development policies themselves, thanks to a capillary information exchange and the possibility to harmonize processes. Tools to build and strengthen capabilities Some of the powerful instruments for enhancing LED processes and strategies

are: Local Economic Development Agencies The LEDAs will help to create territorial added value and social inclusion: industrial products from raw materials, tourism and industry from natural resources, economic activities from local culture and environment and helping the most disadvantaged people to enter into the economic mainstream. The main services provided by the LEDAs are illustrated in figure 2. Fig. 2 Value chains A farmer that grows fruits and vegetables and then, together with other farmers of the area, sells his produce directly to the consumers or to local processing companies has certainly a lower risk to be left with no income: on the contrary his chances to sell increase, particularly when fruits and vegetables are typical of the area and recognized as such. A small bakery that is part of the tourist value chain (the basket of local goods and services available for tourists) has a better chance to survive than one that sells only to local consumers. This can be translated in the creation of territorial value chains, networks of businesses and activities, each one adding value to initial and intermediate products and making the resource to be optimized more competitive. In this context the poor have many more chances for inclusion in the local labour market, even when they want to develop small entrepreneurial activities, since they are an active part of an integrated system of economic supply. Territorial marketing The necessity to present an integrated supply that optimizes tangible and intangible resources of the area (see figure 3) becomes imperative for endogenous development, particularly in those areas where local actors do not have enough resources to promote themselves individually. This translates into the planning of territorial marketing strategies that, around a unifying symbolic value, define the character of the area (water, sun, culture, historical heritage, acceptance, entrepreneurial or working capabilities, agricultural resources, etc) help qualify the image of that area and help communicate it to the outside (through advertisements, publicity, public relations, direct marketing and ad hoc events). Fig.3 Tangible and intangible elements of a territory

Territorial innovation systems But innovation is nothing more than a tool to be used to improve quality of life and as such it responds to a vision and a strategy shared by local actors, using multi-dimensionality and territoriality as indispensable paradigms for action and success. At the same time, innovation is necessarily linked to actions of a national and international dimension, in the production both of knowledge and experience, and of policies to improve the human condition. Innovation shall then be oriented on the one hand to encourage highly

participatory local innovation systems finalized towards collective learning,

and on the other, to work simultaneously on several fronts: Continuing education Primary and secondary education itself should reflect the culture, and what we have called the personality and the spirit of the place in order to strengthen the elements of belonging and active citizenship, fundamental for policies of economic development. Adult education should respond to agreed development strategies, so that it becomes one of their irreplaceable tools. International partnerships A two-level agreement has always been a factor of success for partnership: a political-institutional level between local administrations of the two areas, in order to grant time sustainability and institutional support, and an implementation level with structures such as development agencies, territorial pacts, local action groups or thematic parks, capable of implementing operational activities. The tools here described can strengthen the capabilities of local actors in pursuing the above-mentioned strategies, according to the scheme presented in figure 4. Fig. 4 Strategies, Capacities and Instruments for human territorial economic development

(+) in a highly determining way |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References * Sergio Boisier, chilean, PHD in Economics, U. de Alcalá, Executive President, Centro de Anacción Territorio y Sociedad (CATS), a private consultant firm. ° Giancarlo Canzanelli is coordinator of ART ILS LEDA, UNDP/UNOPS, Italy 1. Supported, for example, by Froebel, Heinrichs and Kreye; Henderson and Castells, and Amin and Robbins. 2. Represented by authors such as Piore and Sabel; Porter, Scott and Storper; Stöhr, Vásquez-Barquero, Garofoli, Cuadrado-Roura and many specialists from Latin America - including the present authors - and from the South in general. 3. That have used various acronyms: Prodere, PDHL, APPI and the present ART Initiative (Articulating thematic and Territorial Networks). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Universitas Forum, Vol. 1, No. 1, December 2008

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Universitas Forum is produced by the Universitas Programme of the KIP International School (Knowledge, Innovations, Policies and Territorial Practices for the UN Millennium Platform).

Site Manager: Archimede Informatica - SocietГ Cooperativa

В